|

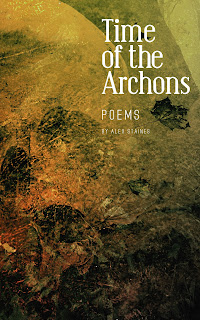

| Book cover illustration by Nihil.One. |

'The air had a face and an inert hand'

Time of the Archons is my fourth book of poetry, now available on Amazon as a Kindle e-book. It continues, with a few modifications, the "cut-up" method, as well as the alexandrine verse structure, introduced in the previous volume, Seclusion Data (2010). (An alexandrine is a 12-syllable line adapted from French heroic verse.)

In this foreword, which I'll be adding to and editing over time as new ideas occur, I'll attempt (for the first time) to outline how I write poetry, and also why - using this latest book as an example.

Expressionism and a painterly way to write

Poetry for me is a mode of artistic expression that can paint ideas, moods, journeys, and characters, subject to few constraints save the indulgence - and attentiveness - of the poet. I purposely use the word "paint", as the way I create poems is more akin to the way a painter works than someone who is primarily interested in using language to convey meaning.I identify with this quote from the French artist Jean Dubuffet:

"As an instrument of expression, [written language] seems to deliver only a dead remnant of thought, more or less clinkers from the fire. As an instrument of elaboration it seems to overload thought and falsify it."1German expressionism is the label for the artistic response at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th, to the alienation of the machine age (Blake's "dark satanic mills"), whereby the inner response to reality is given primacy at the expense of surface appearances. Expressionism was heavily influenced by the "symbolist" poet Charles Baudelaire, by Vincent van Gogh, and of course, Edvard Munch (The Scream). The First World War intensified everything, including for artists involved like Kirchner and Beckmann. The experience of this war also played a role in the overdose death in 1914 of one of the great poets, Georg Trakl, born in Mozart's home town of Salzburg in 1887. Trakl's poems are dark and dramatic. The grotesque details of his brief incarnation as the "Teutonic Rimbaud" tend to cloud the view of a poet who casts a very long shadow over 20th century German literature, some claim to a greater extent than that of his (justly) celebrated near-contemporary, the Prague-born Rainer Maria Rilke.2

I appreciate the Antipodean version of expressionism in painting through the work of New Zealand artists Philip Clairmont, Tony Fomison, Allen Maddox, and Bill Hammond. This group of painters was taught at Ilam Art School in Christchurch by Lithuanian-born artist Rudi Gopas, who emigrated to New Zealand after World War 2, bringing with him the passionate introspection and techniques of German expressionism.

In expressionist painting, a defiant, individualistic attempt is made to recover a wholeness that has been lost - in poetry, Rimbaud's la vraie vie est absente ("the true life is absent"). Frequently, there is an oscillation between what is forbidden and its revelation, between diagnosis and palliative. Perceived opposites of various kinds (profane and sacred, domestic and political, horror and delight) are placed within the same frame. Attempting this kind of "expression" can be an ambivalent and high-risk venture, as the case of Nietzsche bears out. And it was writer Thomas Mann who contributed the idea that German expressionism and Nazism sprang from the same root of emotional self-abandonment. However, Mann was severely repressed.

Georg Trakl wrote about the consequences of his creative attempts to discover the ground of reality - the absent, true life. Trakl's poetry is characterised by unusual, rapid alternations between between the horrific and the sublime, as if the poet needed to subordinate himself to polar extremes in order to bring into the frame aspects of their greater unity. Yet Trakl found this unity to be "unspeakable".3 Expressionists have passionate ideas that spring from the war between faith and reason, not based on abstract thought:

“... in the depths of the abyss, the despair of the heart and of the will and the scepticism of reason meet face to face and embrace like brothers”.4

What is this lost wholeness? The expressionist painters, and their few literary travelling companions, saw that what had been lost was innocence, or rather the artistic relevance of innocence that had been so much a part of the Romantic quest for sublimity. In Merlin's words:

"The spirits of wood and stream grow silent. It's the way of things. Yes... it's a time for men, and their ways."5

In 2017, when I write this, in the age of standardisation and self-improvement, of "men and their ways" (Archons), expressionism is an embarrassment - "instinctively associated with all the worst kinds of narcissism and theatricality".

1 The Resurrection of Philip Clairmont, by Martin Edmond, Auckland University Press, 1999, page 188.

2 Rudi Gopas - A Biography, by Chris Ronayne, David Ling Publishing, 2002. Song of the Departed - Selected Poems of Georg Trakl, transl. Robert Firmage, Copper Canyon Press, 2012. The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, transl. Stephen Mitchell, Picador Classics [1987].

3 Rimbaud - Complete Works, Selected Letters, transl. Wallace Fowlie, University of Chicago Press, 1966. Nietzsche - Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, by Walter Kaufmann, 4th edn, Princeton University Press, 1974.

4 Tragic Sense of Life, by Miguel de Unamuno, transl. J E Crawford Flitch, Dover Publications [2014], page 106.

5 Excalibur, 1981, feature film, written by Rospo Pallenberg and John Boorman, based on the 15th century Arthurian romance Le Morte D'Arthur, by Thomas Malory.

[to be continued, including:]

- Munch, Andersson, St-John Perse, Hamsun, Celine.

- Menippean satire, its offspring, and duende.

- What do we tell them? - disclosure and Ed Ruscha.

- Intentionality, existentialism, the outsider.

- Cut-up and Walter Benjamin.

No comments:

Post a Comment